A

paper published by C. Perreault and S. Mathew in PLOS ONE outlines a

new method of dating the origin of language in Africa, and therefore

the origin of language of all humans.

The

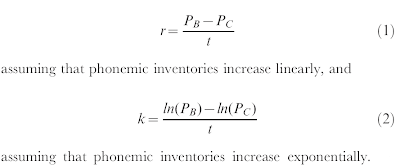

method starts by first estimating a linear (r) and exponential (k)

rate at which phonemic diversity increases with time using this

formula:

Where

t is the date of colonization and PB and PC are

the current phonemic diversity of populations B and C, where such

populations are hypothesized as follows:

"consider

the hypothetical case of two small populations, B and C, that

dispersed from the same parent population, A, t years ago (Figure 1).

Suppose that B and C are similar in size so that they both experience

approximately the same loss in phonemic diversity due to the founder

effect. Now, suppose that population B colonizes a large continental

territory and subsequently expands and diversifies linguistically

[66,67]. In contrast, population C settles on a small island that

does not allow for population expansion and language diversification.

Because of the differences between the regions colonized by B and C,

population B will accumulate phonemes at a faster rate than

population C. Furthermore, if population C evolves on a sufficiently

small island and remains isolated for most of its history, then the

rate of phoneme accumulation in C will be low, and its phonemic

diversity will remain approximately stable through time.

Consequently, the present-day difference between the phonemic

diversity of B and C can be attributed to the new phonemes

accumulated within population B. Thus, the current phonemic diversity

of population C has remained through time a good approximation of the

original phonemic diversity of population B."

They

then use the case of Southeast Asia (Pop B) and the Andaman Islands

(Pop C) to estimate the linear and exponential phonemic diversity

increase rates. The date of colonization, t, of these geographic zones is

set between 45 -65 KYA, the phonemic diversity of Pop B and and Pop

C were retrieved from the UCLA Phonological Segment Inventory

Database (UPSID) and customized with the following assumptions:

"We

estimate PB by taking the average phonemic inventory size

of the languages in Mainland Southeast Asia. Assuming an eastward,

coastal migration route, we have excluded the Asian languages that

are located west of Andaman Islands (such as the languages from India

and Nepal), as well as those spoken in Myanmar and the Malay

Peninsula, because they could have served as departure points for the

colonization of Andaman Islands (Figure 2). The 20 languages retained

in our sample are thus those spoken in Cambodia, Vietnam, Laos and

Southwest China (Table 1). The average phonemic diversity of the

resulting sample is 41.21+2.74 (errors represent one standard error).

Great Andamanese (ISO 639-2:apq) is the only Andamanese language to

appear in UPSID. Its phonemic diversity, 24, serves as our estimate

of PC."

Thus,

with the above values the linear and exponential rate of phonemic

diversity were estimated to be between 0.26-0.38 and 83.17-120.14

respectively for a date of colonization of between 45-65 KYA, where

the lower rate of increase in phonemic diversity corresponds to the

upper bound of the date of colonization and the higher rate

corresponds to the lower bound of the date of colonization.

Next, they proceed to use the rates from above to estimate t0 or “the

time it would take for a language to acquire the phonemic diversity

observed today in African languages” using the following formula:

Where

Pinitial is the number of phonemes that the first human

languages started with, and assumed in one case to be 11, or the

smallest phonemic inventory ever observed and for another case, 29,

or just a median phonemic diversity. PAfrica is the

average of the phonemic diversity of click speaking Africans, as they

are the populations that are thought to have lost the least amount of

phonemes due to founder effect, where as all the remaining macro

language groups of Africa; Afroasiatic, Nhilo Sahran and Niger

Kordofanian are known to have all undergone serious geographic

expansions. The authors substantiate this assumption by stating:

"This

idea is consistent with the fact that the average phonemic diversity

of Afro-Asiatic, Niger-Congo and Nilo-Saharan languages is 36, 33,

and 29 respectively, while the average phonemic diversity of African

languages outside these families is 75."

Using

a few other criteria they therefore estimate PAfrica to be

71.4

Thus

with the above values, the results of t0 for the two

different assumed values of Pinitial were calculated for

the linear and exponential rate of phonemic diversity increase as

follows:

The

authors come to the following conclusion from their analysis:

"Our

analysis suggests that language appears early in the history of our

species. It does not support the idea that language is a recent

adaptation that could have sparked the colonization of the globe by

our species about 50 kya [1,91]. Rather, our result is consistent

with the archaeological evidence suggesting that human behavior

became increasingly complex during the Middle Stone Age (MSA) in

Africa, sometime between 350– 150 kya [92–100]. However, we

cannot rule out the possibility that other linguistic adaptations,

that are independent of phonemic evolution, arose later and triggered

the out-of-Africa expansion."

More

details from the paper, which is open access, can be found here.

The assumption that phonemic diversity changes in only one direction is pretty definitively known to be incorrect. On this faulty assumption, the entire tower of logic crumbles.

ReplyDeleteWhen human populations left Africa, they went through a series of bottlenecks known as the serial founder effect, this is supported with genetic as well as phenotypic diversity decreasing the further modern human populations are found from Africa, phonemic diversity loss seems to be just another parameter that also played out with the serial founder effect phenomenon.

DeleteThe problem is that phonemic diversity loss isn't a secular trend. Phonemic diversity increases sometimes as well. For example, in the Americas, the languages of Mesoamerica that are heirs of the Mesoamerican Neolithic have more phonemes than the languages of the hunter-gathers surrounding them (and more grammatical complexity as well).

ReplyDeleteClaims of reduced phenotypic diversity also freuqently ignore the additional effective phenomes that result from having lexically tonal v. grammatically tonal v. atonal languages. The data is also corrupt. Different linguists looking at the same language after indepth study often reach different conclusions as to the number of phonemes in that language (with the more knowledgable linguist often producing the larger number).

The evidence that phonemes are areal, rather than something related to linguistic origins is pretty good (phoneme isoglosses are not a good fit to language family isoglosses, for example, at the boundaries of African language families). And, there is some evidence that temperature and altitude and geographic context (mountains v. plains v. jungles) influence the phoneme structure of a language far more than its origins.

Andrew, I suggest you read the following response by Atkinson to criticisms on the idea that Phonemic diversity loss has similar patterns with that of genetic diversity loss outside of Africa:

ReplyDeleteResponse to Comments on “Phonemic Diversity Supports a Serial Founder Effect Model of Language Expansion from Africa”

Etyopis, you're a victim of stereotypes. Genetics hasn't furnished any direct evidence for a serial founder effect from Africa. It's a model based on "kitchen logic" that a migrant population is smaller than the parent population. Whether this single logic has governed human population history is unknown. It's unlikely so, as the recent, post-1492 colonization of the Americas demonstrates: the New World now has more genetic diversity than the Old World, but it's the most recently populated continent. This is because it has absorbed diversities from every corner of the globe and it's done it in the course of just 500 years. On the level of a single population we see a corroborating picture: e.g., U.S. Basques are no less, if not more diverse, than European Basques (https://springerlink3.metapress.com/content/j761t3751xj252hx/resource-secured/?target=fulltext.pdf&sid=nk5hmhnz0jyr0lk3g0kuc4bf&sh=www.springerlink.com), hence not every migration is accompanied by a founder effect in genetic terms.

ReplyDeleteWe simply don't know how migrations of ancient small-scale foragers impacted their diversities. It's likely that every migrant population sampled close to 100% of diversity of its parent population. If a bunch of migrant populations subsequently mixed with each other and/or expanded, while their parent populations remained stable and/or isolated, you would end up with more diversity in the target area than in the source area.

On the linguistic front, Khoisans have an excess in click phonemes that sit on top of more "standard" phoneme inventory. But the population size of every African foraging group is much smaller than that of pastoralist or agriculturalist Nilo-Saharan or Niger-Congo population. Hence, the number of phonemes can be inversely related to population size. There are many more flaws with Atkinson's and other similar analyses.

You silently assume that model equals fact and then follow Atkinson and others (who aren't even linguists) in using a genetic myth-model as a null hypothesis for the interpretation of phonetic data.

For a more serious approach to modern human origins, see http://anthropogenesis.kinshipstudies.org/.

German Dziebel, are you an American Indian?

DeleteOk, you don't have to answer, just curious as you seem to have a severe problem with the OOA theory and some how think that modern humans originated in the Americas, a place that has been proven several times to be a sink rather than a source for migrating humans.

DeleteIt is not just measures of genetic diversity showing a decrease from Africa to the corners of the world that show humans were conceived and born in Africa, but also the non recombining uniparental markers that show an unbroken link from Father to Son and Mother to daughter. The starburst genetic variance pattern that is especially seen by daughter clades of mtDNA marker L3 also show that the expansion was relatively rapid and swift, this is quite enough to show that populations outside of Africa are descended from a subset of people that once lived in Africa, and whose descendants still live in Africa. Note that I haven't even referenced any archaeological material, which is pretty much null and void outside Africa until about 50KYA.

Consider also the fact that Khoisan people that now inhabit southern Africa show more nucleotide substitutions amongst each other on a full genome-wide basis than say for instance a randomly picked European and Chinese would.

Really, there are mountains of evidence for OOA at the moment.......

Please see www.anthropogenesis.kinshipstudies.org for my background.

ReplyDelete"there are mountains of evidence for OOA at the moment"

The Bible, too, offers "mountains of evidence." To a believer.

"Note that I haven't even referenced any archaeological material, which is pretty much null and void outside Africa until about 50KYA."

This is precisely when some strong signals of modern human behavior begin to appear in different parts of the world. And we're talking about the origins of modern - anatomically and behaviorally - humans, as all living humans are both and no modern human group is one or the other. Prior to 50K, modern human behavior is problematic everywhere (Neandertals and Middle Stone Age Africans show similar signs of "culture"), hence all those "anatomically modern humans" in Africa may not necessarily be our ancestors. We would need ancient DNA to ascertain their relevance, but we don't have and will unlikely get it anytime soon.

"the non recombining uniparental markers that show an unbroken link from Father to Son and Mother to daughter."

There are many ways in which mtDNA and Y-DNA genetic trees can be constructed. And if you look at X chromosome, you'll see that American Indians have basal lineages at worldwide highest frequencies. And B006 was ascertained in Neandertals. http://mbe.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2011/01/25/molbev.msr024.short

"Khoisan people that now inhabit southern Africa show more nucleotide substitutions amongst each other on a full genome-wide basis than say for instance a randomly picked European and Chinese would."

So what? They maintained typical non-African alleles plus have begun to develop new ones missing from Europeans or Chinese. The opposite logic creates a bizarre situation in which the Khoisans split from the rest of humanity some 100,000 years prior to the emergence of modern human behavior in the archaeological record. But then the Khoisans are no less modern than other human populations. Does it mean they arrived at being behaviorally modern independently of other humans? Khoisans probably entered Africa as a small foraging group some 40,000 years ago and then began mutating at a faster rate due to local demographic/selective pressures. They added clicks to their phonemic inventory and some unique mutations to their genome.

Onur, I don't know who you think you are, but you are not welcome to use colonial age craniofacial classifications to crudely identify populations (more especially in a genetics context) on this blog. Please find another place on the internet that will allow you to indulge in your Victorian age fetish, frock coats and top hats included, this is not a museum, so next time you decide to indulge in said fetishes on this blog, I will delete your messages with no warning.

ReplyDeleteGerman Dziebel I will provide specific answers to your comments when I get a chance.